The stage is set

Published 9:51 pm Tuesday, April 9, 2013

From an illustration of wartime Suffolk that appeared in Harper’s Weekly in May 1863, looking south from the present site of Wendy’s on North Main Street, one can see the Nansemond River in the foreground, with the town beyond. Note the gunboat in the river and the signal tower in the background.

By Kermit Hobbs

Special to the News-Herald

To mark its 150th anniversary, from Wednesday through May 4, the Suffolk News-Herald will feature a multi-part series by Suffolk historian Kermit Hobbs detailing the 23-day Siege of Suffolk.

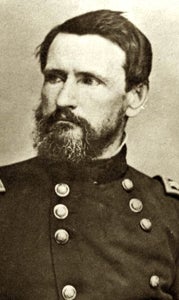

Friday, April 10, 1863 very likely would have found Maj. Gen. John J. Peck, commander of the Union forces occupying Suffolk, pacing back and forth in his headquarters at the home of Nathaniel and Missouri Riddick, today known as Riddick’s Folly.

Gen. Peck had received reliable information that a strong force of Confederates, commanded by Gen. James Longstreet, was planning to attack his forces in Suffolk. Now on this day, he heard that the Confederates were building bridges over the Blackwater River and that Longstreet was bringing a force of 40,000 to 60,000 men. An attack seemed imminent.

For nearly six months, Peck had had the nearly 15,000 troops under his command building a chain of earthwork defenses that stretched 10 miles, completely encircling the town of Suffolk. Those defenses included a dozen forts and artillery batteries, along with a continuous line of trenches connecting them. All the woods outside the defensive line had been cleared so there would be no cover for any invading force. Only the two easternmost forts, Fort Halleck and Fort Jericho, were still unfinished.

Two Union gunboats, the Smith Briggs and the West End, lay moored in the Nansemond River at the present Hilton Garden Inn site, ready to help repel any enemy invasion.

Peck had even set up a sophisticated communications network with a 70’-tall signal station atop the old Masonic Hall on Main Street. From this location, other signal stations had been built in rows, extending in each of several directions out of the town. From the outermost signal stations, some of them miles away, messages could be sent by flag-waving signalmen who would then relay them to the central station at the Masonic Hall.

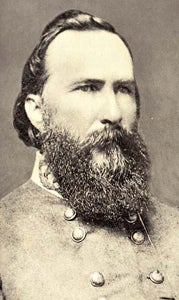

Gen. James Longstreet, now west of the Blackwater River, also might have been feeling the excitement of his impending advance upon Suffolk.

Longstreet had proven himself in battle on many occasions and had earned the trust of his superior, Gen. Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, who referred to Longstreet as his “old War Horse.” The mission to Suffolk would Longstreet’s first independent command. There seems to have been some uncertainty in his mind about the Suffolk campaign, but Lee and his superiors had complete confidence in Longstreet.

If Longstreet had reason to be nervous, it was probably because his mission was so poorly defined. Several months earlier, it had come to the attention to the Confederate authorities that the counties south and west of Suffolk, both in Virginia and North Carolina, were rich in food other supplies that were desperately needed by the Confederate army. Hunger had always plagued the Confederate armies, and two years of war had already depleted the other resources they had relied upon. The idea was proposed that Longstreet’s Corps might be sent to bottle up the Yankees in Suffolk and to clear the countryside of purchasable supplies in those counties in a campaign that would be expected to last about two weeks.

Sometime later, a buildup of Union forces at Fort Monroe had raised suspicions that the Federals might be planning a drive up the south side of the James River, in an effort to capture Richmond. Having Longstreet at Suffolk could prevent this from happening and protect Richmond.

It all seemed to fit together, especially considering that Longstreet could possibly strike a blow at the Yankees while he was in position at Suffolk. He could inflict some damage upon them, and possibly even capture the town.

One more condition was imposed upon Longstreet that would make his mission especially difficult. He was instructed to be ready, on very short notice, to withdraw his entire invading force and rejoin Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

It was getting late in the winter/spring, and the roads would soon be passable. Lee, in northern Virginia, expected some threats from the Union Army of the Potomac against Richmond, and he knew he would need Longstreet’s Corps — one third of his army — back to help defend Richmond.

With these overlapping instructions, it would be easy to see how Longstreet might be uneasy.

Tomorrow: The Rebels appear