Rabbit remembers

Published 10:43 pm Thursday, August 29, 2019

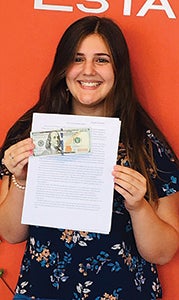

- Rabbit Howard takes a swing(John H. Sheally II photo)

Story by Phyllis Speidell

Photos by John H. Sheally II

Hopping a freight train to school and surviving on charity meals may not be typically fond childhood memories, but one local man can credit the experiences of his hardscrabble beginnings with shaping him into a well-respected educator and a locally legendary coach at Portsmouth Catholic, Churchland and Western Branch high schools.

Now 88 and comfortably retired in Churchland, Ernest “Rabbit” Howard looks back on his life and reflects, “Whenever my own foolish choices slammed a door, a window opened” — one of his numerous life adages, often earned the hard way.

Quick and agile, Howard is a World War II and Korean War-era Army veteran, a natural athlete and a survivor. He turned difficult, often dire, situations into success stories with a resilience that grew from his childhood in Newtown, then one of the poorest sections of Portsmouth.

The early 1950s construction of the Downtown Tunnel decimated Newtown, but the neighborhood lives on in the memories of those with roots there. They remember the poverty, but also the closeness, of the residents. Many of them worked in the Norfolk Naval Shipyard and many others, Howard remembers, owed their survival to the Salvation Army.

“The Salvation Army carried us through the Depression, and I still can’t pass up a Salvation Army kettle,” Howard said.

The Newtown he remembers had a grocery store, Thomas Jefferson Elementary School, a public playground and Bray’s pharmacy. The iceman and “Joe the baker” still made their deliveries via horse and wagon. Few, if any, doctors practiced in Newtown, so residents relied on Bray’s to treat their ailments. Howard also remembers neighbors coming to his paternal grandmother, who was half Nansemond Indian and known for her natural cures.

He and his younger sister, Shirley, lived with their grandmother.

“She was already aging when she raised us, but she had me on my knees every night, praying,” he said. “Every afternoon, she sent me to the shipyard when the Navy chefs set out all the day’s leftover food on long tables and we lined up with our pails to get our share. It was the 1930s Depression way of feeding the hungry and might be where the phrase “pot luck” came from.”

“The Navy yard was hiring three shifts a day and my grandmother rented out rooms, sometimes the same room to a worker on each shift,” Howard added. “I never knew what I would find when I came home.”

At 11 years old, he was selling newspapers and shining shoes. At 14, he was a sparring partner and corner man for a local boxer. When another fighter on the smoker program at Norfolk’s old Center Theater failed to show, Howard found himself, in borrowed trunks and sneakers, facing a Navy boxer, a ship’s champion.

“After one minute, 34 seconds, I hit the floor and all the lights on Granby Street went out.” Howard said. “I woke up at the eight count and the ref had his hand on my back, holding me down — he saved my life. I earned $7 that night and six weeks later, I went back. Overall I won two matches, but lost a lot more.

“Living in Newtown you never realized you were poor until you left,” he said. His realization came when he attended Woodrow Wilson High School with more affluent students.

“It was a long walk to Wilson, so we hitched rides on the freight train that ran right near the school. The officials kept trying to throw us off the train, but we got to be pretty good at avoiding them,” he said. “At Wilson, I was just ‘that Howard kid’ with too much to do at home and without the right clothes or interest to fit in.”

He dropped out early in 1946 to join the Army. When his clumsily altered birth certificate didn’t work, he enlisted for a two-year hitch with a draft card for which he had fibbed about his age. He was 15 years old and, he remembers, “They needed bodies in Europe.”

Months later, while he was in uniform in Germany with the Infantry’s 16th Rangers, his grandmother received truancy notices from Wilson High School.

”The German Army had surrendered, but no one else had, and we were fighting the remaining active Nazi cells and German youth gangs, cleaning up the mess after the army surrendered — something like Afghanistan today,” he said. “I still get upset about people thinking the Holocaust never happened, that it’s a myth. Near Munich, I stood in front of the ovens, smelled it, saw the bodies outside. Our job was to blow it all up until someone stopped us, saying it would be turned into a museum.”

Discharged in March 1948, he came home to Portsmouth and, briefly, Wilson High School. As a 17-year-old freshman, he had “graduated from spitballs,” and dropped out again.

On a trip to Chatham, with a friend who hoped to attend Hargrave Military Academy, Howard decided to use his GI Bill to go there as well.

“I went home, packed my Army duffle bag and took a Greyhound bus back to Chatham,” he said. “The school set me up with used uniforms and a new dress uniform. I had been a sergeant in the Army but at Hargrave, I was the ragtag cadet, a private with upperclassmen telling me how to stand at attention. I was patient with it all, because I knew this was my last chance and that you cannot lead if you cannot follow.”

In 1950, he was in summer school, catching up academically, when North Korea invaded South Korea and, as an inactive reservist, he was recalled for 21 months of active duty. He helped train new recruits in the 11th Army Airborne. Months later, shipped back to Germany as a radio operator, he was often the only enlisted man among officers who encouraged him to finish his education.

After his 1951 discharge, he graduated from Hargrave and went on to Virginia Tech and Richmond Professional Institute, now Virginia Commonwealth University, all on the G.I. Bill. He married Mable, the love of his life, when he was 20 and worked as a night janitor, a drug store clerk, a copy boy at the Richmond Times-Dispatch, in the Dan River textile mill and in a commercial bakery. He credits Mable with seeing him through what he believes was a PTSD-like condition from his first two years in the Army.

Education finally completed, he, Mable and their two daughters moved to Portsmouth in 1959. He taught physical education and coached basketball at Portsmouth Catholic High School, where he started a baseball program. In 1963, he moved to Churchland High School to teach geography and coach boys’ basketball. The principal, Frank Beck, asked that he start a golf program there.

“I didn’t even own a set of clubs, and my players taught me to play golf,” Howard remembers. “Elizabeth Manor was our home course and on my first shot, I put the ball into the pro shop. The players laughed, but we won the state championship.”

In 1968, Western Branch High School opened. Howard and Art Brandriff both left Churchland High to join the new school’s faculty. Howard joined to teach government and coach basketball, cross-country and golf, and become the athletic director. Brandriff, who served as assistant principal and principal for 40 years at Western Branch, remembers that Howard made an impact because “Rabbit is a people person, thought a lot of the kids and understood the game.”

“Everybody loved Rabbit,” agreed Ann Klein, the long-time Western Branch High school secretary. “He really cared about the kids and his athletes.”

When Howard retired in 1991, he became the night manager at the YMCA in Churchland. When he turned 80, he retired, again, to work at Sleepy Hole Golf Course.

Howard still swings a mean club and enjoys frequent visits and golf dates with his former students. His life has come a long way from that scrappy kid in Newtown, but he cherishes the memories that fueled the journey.