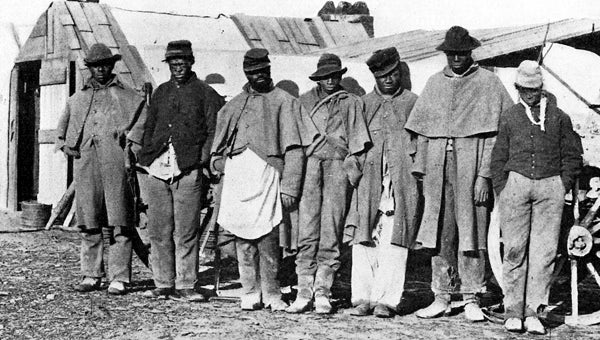

Refugees fill ‘Union Town’

Published 10:35 pm Monday, April 22, 2013

Freed slaves, sometimes known as “contraband,” congregated at Union town settlement in the current Kingsboro neighborhood during the Siege of Suffolk.

To mark its 150th anniversary, through May 4, the Suffolk News-Herald is featuring a multi-part series by Suffolk historian Kermit Hobbs detailing the 23-day Siege of Suffolk.

Part 10: The contraband camp

By Kermit Hobbs

Special to the News-Herald

In Suffolk’s Kingsboro neighborhood by the Nansemond River, there stood an interesting settlement known as “Union Town,” “Greeley Town,” or more often “the Contraband Camp.”

Several months after the outbreak of the war in 1861, three slaves, who had been working on Confederate defenses at Sewell’s Point, escaped during the night and rowed across Hampton Roads to Fort Monroe, which was still in Union hands.

There, they petitioned the fort’s commander, Gen. Benjamin Butler, for refuge and protection from their former owners and from the Confederacy. When a representative of the Confederate army requested their return from Gen. Butler, Butler refused. His rationale was that since the Confederacy regarded the slaves as property, the slaves were “contraband of war,” that is, property of the enemy. The term caught on, and slaves who had run away from their masters and into the protection of the United States forces became known as “contrabands.”

Technically, the name “contraband” became obsolete after Jan. 1, 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation declared freedom for slaves from states in rebellion. Those former slaves were no longer “contraband,” they were freed slaves. Still, the word, “contraband,” continued in use.

Before and during the Siege of Suffolk, able-bodied freed slaves worked alongside Union troops, constructing fortifications. Many of them later joined the United States Colored Troops of the Union.

Across the south, such refugees flocked to areas under Union control, and dozens of such camps were built and survived until after the war. The one in Suffolk was probably begun soon after the Union occupation of Suffolk began in May, 1862. A year later, the population of the camp was estimated to be more than 2,000.

According to one Union infantryman, “A large camp had been established for (the contrabands), and laid out in streets. They proved themselves quite expert in building their temporary homes, riving out material for their construction from the pine and other growths of timber in the surroundings. Schools were established for the children and the activities of a well ordered community were set in motion.”

Another soldier remarked that some of the houses “were built of split pine, thin and larger than our clapboards, and the style of the exterior of some of them would be credible to a summer resort like Martha’s Vineyard.”

R.W. Rock of the 11th Rhode Island Infantry wrote, “some twenty-five of us walked over to Uniontown, not far from our camp, on the banks of the river, entered the large chapel of the contrabands and remained standing while they carried on their worship, for more than an hour and a half. The building was crowded with colored people of all ages and shades. There were old and gray-haired men and women, numberless children, and infants at the breast all engaged in worship with the utmost intensity and earnestness.”

“The dresses were in the most wonderful and fantastic variety; the manifestations unsuited to any other place. The singing defied all description. If we should attempt a description of what we saw we should be open to the charge of fun-making; yet it was one of the most serious and affecting religious assemblies the writer ever attended. They sang frequently, the melodies set to the most singular words. Some of the tunes were lively and adapted to dancing, but most of them were very plaintive in their character. The Jubilee singers have given us the only specimens of the peculiar music of these ex-slaves and their plantation melodies. The choruses were powerful and moving. An exhortation of an elderly gray-haired brother was full of pith and point, and would not disgrace a better educated mind. It was a regular plantation conference and prayer meeting, to be enjoyed only south of the Mason and Dixon’s line.”

Friday — Part 11: Fraternizing with the enemy