A three-hour stalemate

Published 10:19 pm Thursday, March 8, 2012

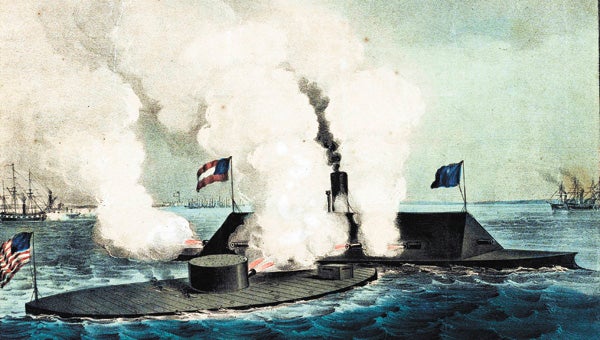

The famous lithographers Currier & Ives took a decidedly slanted approach to their depiction of the Battle of Hampton Roads, which most historians say was a stalemate between two of the world’s earliest ironclads. The subtext under the title of their famous work of wartime art reads, in part, “In which the little ‘Monitor’ whipped the ‘Merrimac’ and the whole ‘School’ of Rebel Steamers.

After a day of pounding the federal fleet into submission, the CSS Virginia — known as the USS Merrimack in her former life as a federal steam frigate — spent the night of March 8, 1862 docked at Sewell’s Point, giving the Confederates a chance to resupply and recuperate from the noise and stench of the enclosed ironclad steamer.

They had left the frigate USS Minnesota where it had run aground on a shoal at the mouth of the James River during the battle, and they headed out at 7 a.m. on March 9 to finish the job that a sinking tide had prevented them from accomplishing the previous night.

What they hadn’t expected, though, was another ironclad ship in the waters of Hampton Roads that morning. That ship, the USS Monitor, had arrived on station after the battle the previous evening and patrolled the area at the mouth of the James, where folks from Suffolk could see from Pig Point — which is now the old TCC campus — the historic and epic battle that would ensue between the two vessels.

Unlike the Virginia, which had been rebuilt to be an ironclad, the Monitor was purpose-built. It was, therefore, smaller, lighter, had a shallower draft and was more maneuverable. It also had a rotating turret with two guns, giving it almost unlimited mobility to fire at targets.

The Virginia’s battle would not be so easy on March 9 as it had been on March 8.

Lt. Catesby ap Jones, who drew the assignment to fight the second-day’s battle upon the injury of Capt. Franklin Buchanan the previous day, soon found himself and his crew facing a formidable adversary in the vessel the rebels thought looked like a floating cheese-box.

From Jones’ account of the battle, in the Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. XI: “The Monitor commenced firing when about a third of a mile distant. We soon approached, and were often within a ship’s length; once, while passing, we fired a broadside at her only a few yards distant. She and her turret appeared to be under perfect control. Her light draft enabled her to move about us at pleasure. She once took position for a short time where we could not bring a gun to bear on her. Another of her movements caused us great anxiety; she made for our rudder and propeller, both of which could have been easily disabled. We could only see her guns when they were discharged; immediately afterward the turret revolved rapidly, and the guns were not again seen until they were fired. We wondered how proper aim could be taken in the very short time the guns were in sight. The Virginia [Merrimac], however, was a large target, and generally so near that the Monitor’s shot did not often miss. It did not appear to us that our shell had any effect upon the Monitor.”

Soon, Jones decided to ram the Monitor, a tactic that had sunk the great USS Cumberland the previous day. But the Virginia had lost its iron ramming spar in that encounter, and, in Jones’ words, “(t)he Monitor received the blow in such a manner as to weaken its effect, and the damage to her was trifling.”

In all, the battle between the two revolutionary ironclad vessels, lasted for three hours, with spectators on the banks of the river recalling the scene in vivid detail for historians to recount.

A nearly point-blank shot into a porthole in the pilothouse of the Monitor blinded Lt. J.L. Worden, her commanding officer. There was little other damage to report. The Virginia was dented and suffering engine problems but suffered no severe damage.

The two ships withdrew from the battle around noon. In the course of three hours, naval battles had changed forever.