A grave mystery

Published 8:40 pm Saturday, May 25, 2013

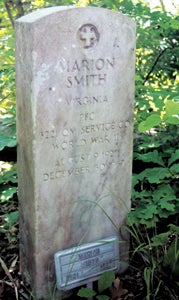

Joe Schipper and Ed Fallen crouch next to the grave of Marion Smith, a World War II veteran, who records show may have taken part in the D-Day landings. Smith’s final resting place is among several neglected graves next to Harbour Breeze Apartments.

Navy operations specialist Ed Fallen was walking his dog one recent evening when something caught his eye.

“I happened to look into the woods and saw what looked like grave stones,” said Fallen, who lives in North Suffolk’s Harbour Breeze Estates.

In a narrow sliver of woods between the western edge of Harbour Breeze Apartments and Mainsail Lane, marooned in suburbia, the graves were overgrown and long-neglected.

Fallen photographed a headstone and posted the picture on his neighborhood’s Facebook page.

Joe Schipper, a Navy veteran and techie at Western Branch High School, saw the photo online and, later that same evening, decided to go take a look.

“There turned out to be about 10 markers” in addition to a couple of headstones, Schipper recounted.

Enjoying a good mystery, and noticing from a headstone inscription that one of the deceased was a Word War II veteran, Schipper started digging — metaphorically speaking, of course.

According to what Schipper unearthed, including a headstone application for military veterans, the 1930 U.S. Census and U.S. Army records, Marion Smith, an African-American, enlisted two days before Christmas in 1942. He was discharged May 10, 1946. He lived from Aug. 9, 1921 to Dec. 30, 1957.

The headstone on World War II veteran Marion Smith’s grave stood forgotten in a strip of woods next to Harbour Breeze Apartments until Ed Fallen, walking his dog, rediscovered it. Fallen and another Harbour Breeze Estates resident, Joe Schipper, wonder if any descendants exist to care for the grave and others scattered around it.

But one significant contradiction emerged from Schipper’s findings.

While Smith’s headstone says he was a private first class in the 3221 Quartermaster Service Company, the headstone application lists the 3455 Quartermaster Truck Company.

The discrepancy is one Schipper hasn’t been able fully resolve, but he has concluded that Smith may have been among the 160,000 Allied troops that on June 6, 1944, landed on the French coast at Normandy to liberate France from the Nazis.

According to records, including from the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, the 3455th was part of the Ninth U.S. Army, which was stitched together from units that had stormed the Normandy beaches.

Smith may have been reassigned after the invasion, Schipper says. Both the 3221st and 3455th are listed as either “colored” or “segregated” units.

Solid confirmation Smith was directly involved in the D-Day landings is lacking, however, and an online Army list of the units involved, omitting both the 3455th and the 3221st, suggests he wasn’t.

Schipper and Fallen are going public with their discovery in the hopes of finding descendants of the dead, if any remain, who might care for the graves.

Both having a military background themselves, they say the fact that one of the deceased was a veteran makes it all the more important.

“No one likes to see a grave forgotten — especially when they served their country,” Schipper said.

In 1930, 7-year-old Marion Smith lived in Sleepy Hole, according to that year’s Census. His parents were Corbett and Marie Smith.

Horrace Goodman, also buried in the forgotten graveyard, was a 37-year-old laborer in 1940, according to another Census — the same occupation as Curtis Gully, interred there also, who was 68 in that year.

Who owns, or did own, the graveyard is another mystery Schipper and Fallen are pondering. The variety of surnames — Gordon, Goodman, Robbins, Stewart, Trotter, Reid and Burke also among them — suggests it isn’t a family plot.

The application for Smith’s headstone cites Bellville Cemetery, but nowadays, Bellville Cemetery is on the other side of Route 17, opposite Temple Beth El, the international headquarters of the Church of God and Saints of Christ.

William Saunders Crowdy, a slave who won his freedom fighting for the Yankees in the Civil War and a Santa Fe Railroad cook, founded the religion.

Followers believe God appeared to Crowdy in a vision while he was in Guthrie, Okla.

Today led by Rabbi Jehu August Crowdy Jr., William Crowdy’s great-grandson, the tenets of the Church of God and Saints of Christ aren’t easily pigeonholed. Believers say they follow biblical Judaism.

In 1903, Crowdy purchased for his church a 40-acre spread at Bellville, a Suffolk place name now largely vanished. The sect later purchased more adjoining land.

Through the years, the Saints — as Route 17 old timers refer to them — have turned over much of the land to development. One theory has it that the rediscovered graves were once part of Bellville Cemetery, but were cut off by the development and subsequently forgotten.

Elder Ezra Locke, co-pastor and general superintendent at the temple, which still owns Bellville Cemetery, isn’t so sure.

He said the names from the hidden graveyard are nowhere to be found in temple records.

“I don’t know if it has a connection to us or not, but I don’t think it does,” he said.

Despite their proximity, the graves are not inside the Harbour Breeze Apartments plot, says Burt Cutright of BECO Construction, its owner.

“I believe if you look at the plat, they are almost certainly part of open space for the (Harbour Breeze Estates) subdivision,” he said.

Jodie Matthews, 58, is the general manager of Bennett’s Creek Farm Market. His grandfather’s farm, which Matthews said was about 2,000 acres in its prime, with the last portion sold in the early 1980s, abutted the temple’s property.

“They were back there on the edge of the farm,” he said of the graves. “Our farm backed up to that. On the other side of the ditch was the graveyard. They were owned by the Saints.”

Matthews recalls the graves in the mid-1960s being set in “nothing but woods.”

“If you were standing there, you’d see the old original road from Churchland,” he said.

No one was looking after the graves back then either, he added.