Suffolk man plumbs slave history

Published 9:43 pm Monday, August 22, 2016

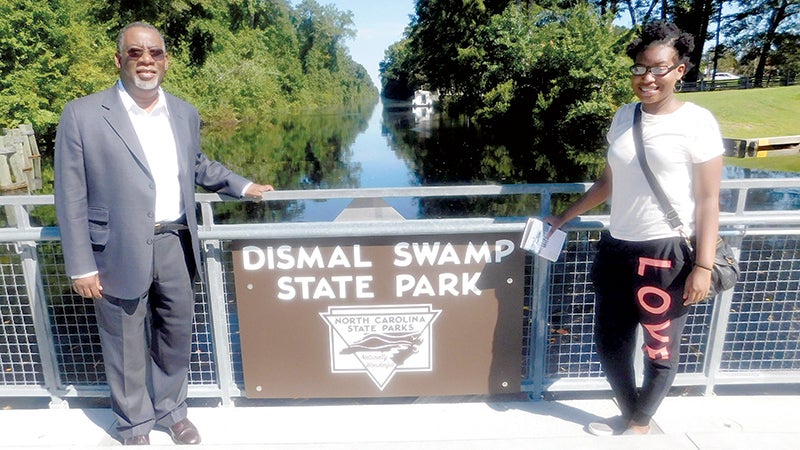

- Eric Sheppard is joined by his daughter, Mackenzie, by the Dismal Swamp State Park Canal.

A Suffolk resident with ties to a former enslaved man who worked on the Dismal Swamp State Park Canal in North Carolina has honored that ancestor in a museum exhibit.

Eric Sheppard, a Baltimore native, took an interest in his ancestry and moved to the Suffolk area. After two decades of research, he learned he comes from the family of former slave, Moses Grandy.

Sheppard discovered that one of his ancestors was Grandy’s brother. Both men were natives of Camden County, N.C. In a museum narrative, Grandy — voiced by Sheppard — mentions that he had several siblings who were sold away or dead when he was very young.

Sheppard eventually got involved with the welcome center at the Dismal Swamp State Park. He lent his voice for the center’s Moses Grandy exhibit.

“If we don’t do something to honor our ancestors’ legacies, who will?” Sheppard said.

Between 1793 and 1805, slaves shoveled the 22-mile canal. The waterway allowed products to be shipped from Albemarle Sound, an estuary along the North Carolina coastline, to the Norfolk harbor.

The slaves had to endure extreme conditions: heat, humidity, biting insects and physical abuse from slave masters.

“It was an environment I’d never want to live in,” said Adam Carver, park superintendent of the Dismal Swamp State Park.

Grandy drove lumber to the canal and also served as an overseer. His knowledge of the canal was critical to the Underground Railroad. In addition to helping lead others to freedom, he spent more than $3,000 to free himself and several family members.

The swamp was a known route for runaway slaves and was home to several maroon colonies. Escaped slaves stayed in these communities awaiting northbound ships to freedom. Historians believe the Dismal Swamp housed one of the largest maroon populations in the nation.

The swamp once spanned more than 2,000 square miles across the Virginia and North Carolina borders. However, due to drainage and manufacturing uses, the park has shrunk to just over 125,000 acres.

In 1992, Sheppard began Diversity Restoration Solutions Inc., to strengthen social and cultural knowledge and relationships in Africa and domestically.

“I feel I’m following a God-given purpose to do this,” Sheppard said.

For the last few years, he has led heritage tours throughout the Hampton Roads and the northeastern region of North Carolina, spotlighting the places highlighted in Grandy’s narrative.

This fall, Sheppard plans to host his first homecoming trip to Africa. During the trip, the group will travel to The Gambia, Ghana and Zambia. Sheppard hopes to develop relationships with the citizens and to start a dialogue about African and African-American history.

“We are not tourists; we are going home,” Sheppard said.

Sheppard hopes to build a restoration center in Zambia. This will serve as a hub for diplomacy and discussion about African ancestry.

Sheppard will host a workshop detailing the specifics of the homecoming trip on Sept. 17 at the Hampton Roads Convention Center. To register for the event, visit www.diversityrestoration.com.