Bringing Douglass to life

Published 11:33 pm Monday, December 25, 2017

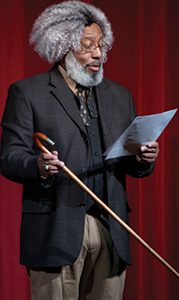

With a frizzy, salt-and-pepper wig and a slightly lower octave, 21st-century poet Nathan Richardson seems to transition effortlessly into 19th-century orator Frederick Douglass.

Suddenly, Richardson is gone and Douglass, who died in 1895, stands before the crowd. He shares about his early life, having been born on a plantation in Maryland and taken from his mother so she could continue to work in the fields.

“I never saw my mother in the light of day,” Douglass says, explaining to a group of youngsters that he grew up on a different plantation, and his mother would sometimes walk 12 miles at night to rock him to sleep and then walk 12 miles back home. She died when he was 6 years old, Douglass says.

In a sonorous, historical, authoritative voice, Douglass explains the rations slaves were given in food — eight pounds of pork or fish — and clothing, which for children consisted of two shirts per year. Douglass relays his excitement at getting his first pair of pants at age 6.

It doesn’t take Nathan Richardson long to get into character when he’s portraying Frederick Douglass. The beard is his own, and the wig takes just a few moments to get right. He has memorized several of Douglass’ more important speeches, and the transformation is quick and convincing.

Douglass doesn’t shy away from sharing the brutal parts of slave life, even with children. One of his earliest memories, he shares, is hiding in a cupboard as his master whipped his aunt for visiting a young man on a nearby plantation.

Later, Douglass shares how he learned to read and write and then yearned for freedom.

“Once your mind is free, your body has to follow,” he says. “You cannot enslave a free mind.”

Wielding a book in one hand and a cane in the other, he tells of his escape to New York and how fellow abolitionists bought his freedom for $733.13. He tells of marriages, five children, running the abolitionist North Star newspaper and working with suffragists to help women obtain the right to vote.

And after a soaring recitation of a condensed version of Douglass’ speech, “What, to a Slave, is the Fourth of July?” he tells the crowd, “Good night. I am Frederick Douglass.”

Douglass, of course, would be 199 years old if he were alive today. Richardson has helped bring the historical figure back to life through his living history presentations.

Richardson first started portraying Douglass about four years ago. He was a thriving poet and spoken word artist when someone else suggested that he add a historical character to his repertoire.

He was intrigued by the suggestion, having long been a fan of Clay Jenkinson’s portrayal of Thomas Jefferson. He began researching some figures but dismissed some, including Booker T. Washington, for various reasons.

When he came upon a photo of Frederick Douglass, he thought he looked the part. But that wasn’t all there was to it.

“When I saw Douglass’ picture, I thought physically I could do it, but could I capture the spirit?” Richardson said.

He pored over Douglass’ autobiographies, speeches and other writings and decided it was a good fit.

“He was very poetic in his writing,” Richardson said. As an advertising representative for the Suffolk News-Herald, Richardson was also intrigued that Douglass was a newspaper man as well.

“There were a lot of things I had been doing all along that set me up for it,” Richardson said. “I didn’t choose Douglass; Douglass chose me.”

Richardson has educated himself on all things Douglass to make sure he knows the man’s intent. He keeps track of lesser-known facts — Douglass was the first black man to be nominated to run for vice president, and his second wife was a white woman, for example — and studies Douglass’ views and their evolution throughout his life.

Richardson loves to explain how Douglass eventually broke with the likes of William Lloyd Garrison, who thought the Constitution was a flawed document and needed to be re-written, and came to believe the Constitution was “a document we should support wholeheartedly.”

“He eventually realized we have the best document in the world and we needed to hold our policies and politicians to those words,” Richardson said.

He has memorized condensed versions of six of Douglass’ speeches and matches them to the theme of the event.

“I take down the fourth wall and accept unscripted questions,” Richardson said.

Richardson said he enjoys his work, especially when he gets to speak to students.

“It’s teaching them about civic responsibility,” he said. “Your vote does not stop at the ballot box. You have to be engaged.”