Dodging bullets

Published 11:18 pm Monday, April 15, 2013

To mark its 150th anniversary, through May 4, the Suffolk News-Herald will feature a multi-part series by Suffolk historian Kermit Hobbs detailing the 23-day Siege of Suffolk.

Thursday, April 16, 1863

By Kermit Hobbs

Special to the News-Herald

By this time it had become clear that a coordinated all-out attack to capture Suffolk was not part of Longstreet’s plan. Perhaps the ring of Union defenses surrounding the town helped him make his decision, or perhaps the task of gathering supplies for the Confederate army was uppermost in Longstreet’s mind.

In either case, the Siege continued to be a deadly game for both sides as men fell victim to sharpshooters’ bullets.

Most of the rifle-muskets used by the armies fired .58-caliber “minie-balls” that were extremely accurate and lethal from hundreds of yards away. A few men carried heavy rifles fitted with telescopes that could hit and kill from a distance of half a mile or more.

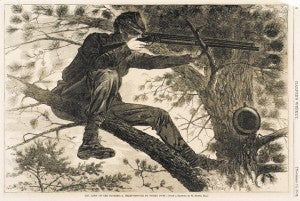

On Nov. 15, 1862, Harper’s Weekly magazine published an etching of a painting by Winslow Homer, portraying a sharpshooter for the Union Army on picket duty. Both the Union and Confederacy relied on sharpshooters during the Siege of Suffolk.

Minie balls had a hollow base and traveled below the speed of sound, so when they whizzed by, they made a distinctive “zip” sound that struck terror in the hearts of people close by.

Private Solomon Lenfest of the 6th Mass. Infantry wrote, “As we were coming in and were almost at Fort Nansemond, the rebel sharpshooters across the river opened on us and one ball whistled between me and the file leader striking the ground close by. It was rather too close to be safe and I think the rebs were very impudent to fire at us when we were not troubling them.”

S. Millett Thompson of the 13th New Hampshire infantry wrote that there was a saying in his regiment, “Show your head — and you are dead.” “A hat held up on a spade brings several bullets and two of them striking the spade are elegantly flattened.”

The 99th New York Infantry’s campground was within sight of the Confederate sharpshooters, and a veteran later recalled their plight. “I was only there about half and hour, and in that time I am sure I could have counted fifty balls coming over us or bounding along the ground. (The) tents are completely riddled, and every time a man shows himself he is sure to be saluted by a little infernal machine. In leaving the rear of a cook house, we had to go across an open space only ten feet, and we were fired at. Fort Rosecrans shells the enemy almost continually, and as sure as they open a gun, the whole line of Rebel rifle-pits starts in. It puts me in mind of intruding upon a hornets’ nest.

Sharpshooters were so vexing to the men in the trenches that heroic actions were sometimes taken to get rid of them.

Confederates manning one of the earthworks overlooking the river were constantly being harassed by Yankee sharpshooters hidden in the marsh on the other side of the river. A Confederate veteran recalled that one Texan “amid a shower of bullets, swam the river and, with a block of matches he had secured on top of his head, fired the bulrushes” where Yankees were hiding, driving them back to their river bank out of rifle range. He added, “To the amazement and joy of all, (he) returned to our lines unhurt.”

William L. Hyde of the 112th New York Infantry recalled that the riflemen of the enemy, posted in rifle pits across the Nansemond, caused them many casualties. They nicknamed one of the enemy sharpshooters whose aim was always fatal, “Old White Hat. “So annoying had he become, that Capt. Arnold gave permission to two of his riflemen to cross the river and try him. Under cover of a tree on the other side, they crossed the bridge (on the railroad) ties. When they came to a place, the crossing of which would expose them, the (Union) artillery opened with shell, and under cover of the smoke they crossed the open space. Then skulking among the stumps, they reached a position from which they pointed their guns towards the pit where “Old White Hat” was. In about twenty minutes he raised his head; they waited a moment and he raised again; they waited till the third time he raised up breast high, then fired. “Old White Hat” gave them no more trouble.”

Friday — Part 7: The surprise attack