‘Historical threads’ tie Hampton Roads to Apache

Published 10:09 pm Tuesday, February 11, 2020

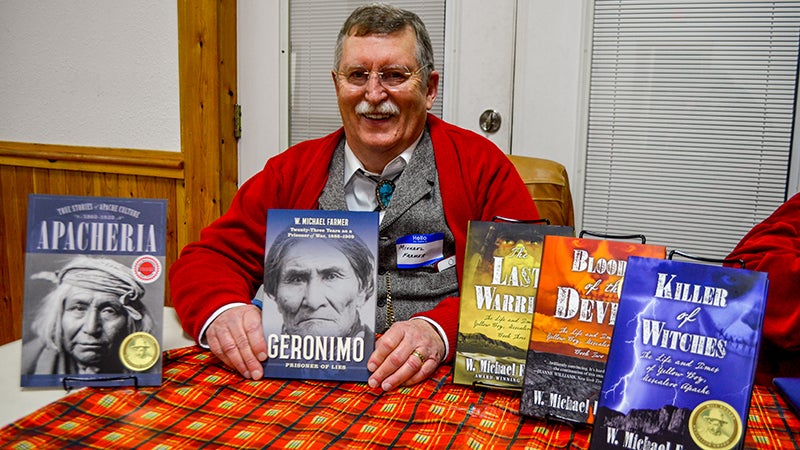

- Dr. W. Michael Farmer signs copies of his books at the River Talk held in North Suffolk on Jan. 21.

At a River Talk presentation in North Suffolk last month, an award-winning author highlighted the historical connections that Hampton Roads has to Chiricahua Apaches.

The River Talk was held on the evening of Jan. 21 at the C.E.&H. Community Hall on Eclipse Drive. The program was organized by the Suffolk River Heritage organization, with Dr. W. Michael Farmer as the guest speaker.

Farmer is an award-winning author and retired physicist who takes more than a decade of research into 19th-century Apache history and culture and combines that research with Southwest living experience “to fill his stories with a genuine sense of time and place,” according to his website wmichaelfarmer.com.

Smithfield resident Darrell Daniels is a fan of Farmer’s books who attended the author’s presentation on Jan. 21. Daniels said that Farmer is a “very interesting writer” who covers subjects that are different from anything else he’s read.

“Once you get into his books, you can’t put them down,” Daniels said, “because his characters are so compelling, and they’re so interconnected.”

More than 30 people attended to hear about the Chiricahua Apache historical connections that go back to Geronimo’s surrender in 1886.

Encyclopedia Britannica states that Geronimo was born in June 1829. He was the Bedonkohe Apache leader of the Chiricahua tribe of Apaches, “a small but mighty group of around 8,000 people,” according to history.com.

“For generations the Apaches had resisted white colonization of their homeland in the Southwest,” britannica.com states. “Geronimo continued the tradition of his ancestors from the day he was admitted to the warriors’ council in 1846, participating in raids into Sonora and Chihuahua in Mexico.”

Geronimo and Chief Naiche, the last hereditary chief of the Chiricahua band, surrendered to General Nelson A. Miles in September 1886. Their band had been chased for five months across the southwestern United States and northern Mexico by 5,000 American soldiers, 3,000 Mexican soldiers and hundreds of civilians.

Geronimo was with 17 of his fellow warriors, 14 women and six children. Not a single member of the band had been killed or captured when he surrendered, according to Farmer’s talk.

Lt. Charles B. Gatewood was the one who tracked down Geronimo and his band in the Sierra Madre Mountains of Mexico. With two Apache scouts, an interpreter and a mule packer, Gatewood risked his life to find and convince Geronimo into accepting the terms of surrender from Miles.

After Geronimo’s surrender, the army moved the entire Chiricahua tribe — nearly 700 men, women and children — to Florida for two years, and then to Mount Vernon Barracks, Ala. for seven years, according to the synopsis.

Farmer also informed his audience of three specific Hampton Roads connections to the Chiricahua Apaches.

The first connection is that Gatewood, the army lieutenant who had convinced Geronimo to surrender in 1886, died in 1896 in the hospital at Fort Monroe.

The second connection is about the Chiricahua children. During their years in captivity, many of these children — along with other Native American children — were educated at the Hampton Normal and Agriculture Institute, later known as Hampton University.

A Native American education program was established at Hampton in 1878 by Samuel Armstrong, the university’s founder, according to encyclopediavirginia.org.

The third connection is that Hampton Roads was seriously considered to be a site for a Chiricahua Apache reservation, based on Armstrong’s proposal in 1888.

“I think that the moral to the story is we’re a lot more closely connected to past events than we … believe, and that it’s invisible, historical threads that tie us all together,” Farmer said at the end of his presentation.