Tragedy on the rails

Published 10:01 pm Friday, February 14, 2020

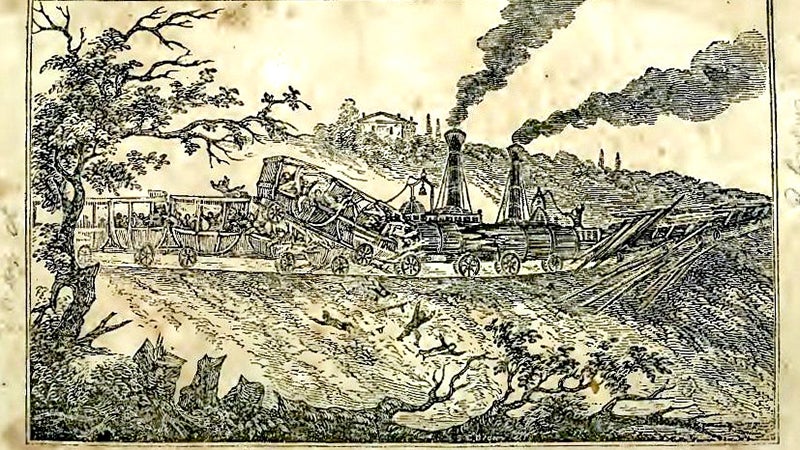

- A woodcut illustration of the Aug. 11, 1837, railroad tragedy that took place in present-day Suffolk. (Submitted Image)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Kermit Hobbs

Special to the News-Herald

Editor’s Note: Kermit Hobbs is the historian of the Suffolk-Nansemond Historical Society.

The opening of the Seaboard Railroad through Suffolk in 1835 must have been a significant culture change for the people of Suffolk. Being able to sit comfortably and watch scenery pass by as they traveled would have been an almost magical experience for people who had never known transportation other than by foot or by horse and buggy.

Railroad travel at the time may have been quick and easy, but as it turned out, it was not necessarily safe. On Aug. 11, 1837, Suffolk people learned just how dangerous it could be. A newspaper of the time gave the following report:

“The daily train with nearly two hundred passengers was run into by a lumber train on the Portsmouth rail-road, in Virginia, August 11, 1837, — by which occurrence several lives were lost, and many were maimed and otherwise wounded.

“The daily train left Portsmouth on Friday, August 11, at 8 o’clock, with thirteen passenger and other cars, and nearly two hundred passengers, the greater portion of who composed a party of pleasure who had been on a steamboat excursion, and were returning to their homes. The train having made its usual stop at Suffolk, had proceeded on to Smith’s Bridge, a high embankment over Goodwin’s Landing, a mile and a half beyond. Here there is a gradual rise in the road, and at the termination of the embankment, the road makes a curve. But before we proceed further, we should state that there was a lumber train then on its way down, with fifteen cars heavily laden with staves, which must necessarily pass the passenger train at one of the turn-outs above Suffolk.

“When the locomotive of the passenger cars had reached the curve, and while the whole train was on the embankment, (which at that place is a greater elevation than any other of the whole line, being thirty-five feet high,) the lumber train suddenly appeared in sight, sweeping down the curve.

The engineer of the passenger train promptly stopped the locomotive, but he of the lumber train was either unable, owing to its being on a descent, to stop his, or did not see the danger in time, for his engine drove furiously on against that of the passenger train, forcing it back upon the first car, which was driven against the second, and the second against the third, and the two latter were crushed to pieces in the dreadful concussion. The greatest havoc, however, was in the second car, the first having been lifted from the rails and propelled over it, raking, as it were, fore and aft, and crushing to death, or horribly maiming the passengers who remained within it. We must leave it to the imagination of the reader to depict the horrors of that awful moment, and of the scene that ensued.”

“The accident occurred within a hundred yards of the residence of Mr. Richard Goodwin, where the dead and wounded were carried. From this kind and hospitable family, as well as from the ladies of Suffolk, the unfortunate sufferers received every attention that could be bestowed.”

This article presents an interesting challenge — to determine the location of the accident.

The Seaboard Railroad follows the same route today as it did in 1837. The train was traveling westward from Portsmouth to Suffolk and beyond. A mile and a half west from the Suffolk depot, the railroad crossed Smith’s Creek, today covered by Lake Meade just west of the Lipton Tea plant on Holland Road. Smith’s Creek was, of course, a tributary of the Nansemond River, and commercial boats did, in fact, travel upriver to this point.

The railroad makes a slight northward bend behind the present Amadas Industries plant, enough to prevent the two approaching locomotives from seeing each other. On the north side of the railroad there is a bluff, as described in the article. The railroad also begins a slight upward incline as it goes on toward the west.

The woodcut illustration accompanying this article is viewed facing southward. In the background is the home of Richard Goodwin, which very likely stood on the hill just west of the Amadas plant. Beyond the residence, out of view of the illustration, ran the South Quay Road, which we now know as Holland Road.

Tragically, two more Suffolk residents were run over and killed as they walked along the railroad in the dark of that evening. Thus, the day’s casualties totaled four killed, 13 severely injured, and at least 25 less severely injured — a horrible day in Suffolk’s history.