The Siege is Lifted

Published 11:02 pm Friday, May 3, 2013

Monday, May 4, 1863

Part 15: The siege is lifted

By Kermit Hobbs

Special to the News-Herald

Late in the afternoon of Thursday, April 30, 1863, Gen. James Longstreet received a message he had been expecting.

He had been ordered to pull out his entire force of Confederates from Suffolk and have them rejoin the remainder of the southern army facing battle against Union Gen. Joseph Hooker’s Army of the Potomac.

In the days after he received that message, the widely scattered Confederate wagon trains, loaded with valuable forage, had been rolling back and crossing the Blackwater River, safely out of reach of the Union forces.

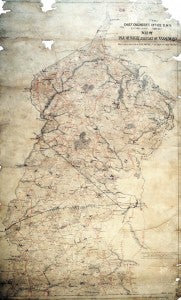

This Confederate map is very likely the one used by Gen. James A. Longstreet to plan the withdrawal of the Confederate army from Suffolk. (Courtesy of the West Point Library, New York)

Longstreet had been carefully planning one of the most difficult of military operations — a safe and orderly withdrawal from an alert and aggressive enemy. Unknown to all but a few of the higher-ranking officers in Longstreet’s army, the withdrawal was scheduled to begin at dark on the evening of May 3.

Even the heavy fighting along Providence Church Road and the lesser activities along the Chuckatuck Road and at Fort Huger that day had not interfered with Longstreet’s plans.

At dark on the evening of the May 3, orders went out to the Confederates along the miles-long line to move out immediately and march to the Blackwater River. There were to be no loud noises made during the withdrawal. Different sections of the army would march by different routes to the Blackwater so as to avoid congestion during the dark hours.

Longstreet had had men partially cut trees next to the roads so that once the soldiers had passed through, the trees could be felled across the roads, hindering any Union pursuit. Pickets were left in position until the last possible moment, guarding the approaches from the Union lines.

Secrecy was absolutely critical to the success of the withdrawal. Even so, two deserters from the Confederate army slipped into the Union lines at around 11 p.m. and betrayed the secret that their comrades were so set on keeping.

The Union reaction was quick. Col. Charles Dodge immediately sent out his cavalry to chase the retreating Confederates. Union infantry was also sent out, but the rapidly moving Confederates were hard to catch.

At around dawn, the cavalry and a small force of infantry caught up with the Confederate rear guard several miles west of Suffolk. Some shots were fired between them, but Union forces were unable to hamper the Confederate retreat.

During the day, they rounded up 40 or 50 stragglers. While they were at it, they burned dozens of civilians’ homes in retribution for their presumed complicity with the Confederates during the siege.

By 2 p.m. on the afternoon of May 4, 1863, the last of the Confederates were across the Blackwater River. They had made a relatively clean getaway. Longstreet’s Suffolk Campaign, known to the Federals as “the Siege of Suffolk,” was over.

Gen. John Peck stated in his official report on the Siege of Suffolk that the losses from his army in killed, wounded, and missing totaled 202. Losses from the Union navy totaled 31. Peck estimated that the Confederates had lost around 1,500 men.

Even allowing for the fact that such estimates were usually much higher than the actual numbers, it is safe to say the losses to the Confederate forces were significantly higher than those of the Union. What makes this more important is the fact that the south’s population was much smaller than that of the northern states, making those manpower losses far more difficult to replace.

Gen. Peck and the Union forces had performed admirably in defending their position and keeping pressure on the Confederates, particularly in capturing Fort Huger and its five pieces of artillery. They continued to believe, as do some historians today, that Longstreet’s primary mission had been to surround Suffolk and capture it. They congratulated themselves on preventing that from happening.

Longstreet’s performance at Suffolk did not earn him much praise, either in his own time or in the eyes of historians. The loss of Fort Huger marked his Suffolk Campaign as less than successful.

On the other hand, he fulfilled his mission of gathering forage his army desperately needed. Those wagonloads of supplies would fuel a new Confederate drive northward, ultimately to the town of Gettysburg, Pa.

The real losers in the three-week ordeal were the civilians living in and around Suffolk. Scores of homes were destroyed by the Union army, both before and after the siege. Even the loss of the food supplies, farm animals and goods purchased by the Confederate army proved painful.

For the civilians of Suffolk and the surrounding counties, the horrors of war would only get worse. For the next two years, their new, very real enemy would be starvation.

Tomorrow: Part 16: Epilogue