Resilient & recognized at last

Published 4:23 pm Wednesday, May 16, 2018

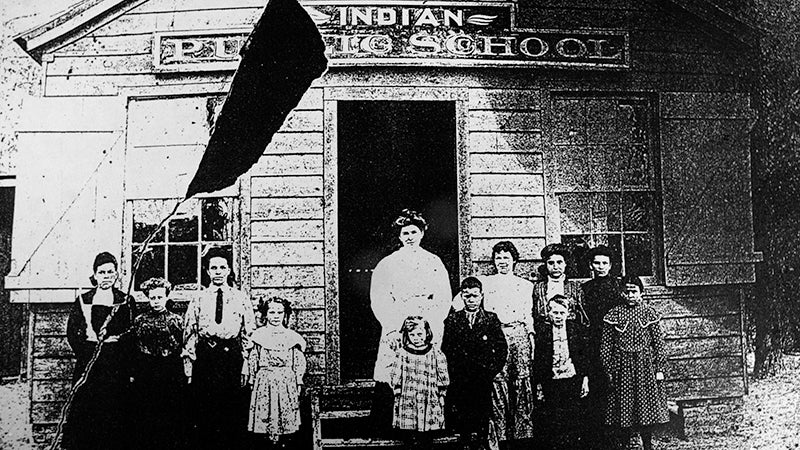

- Indian Public School

Story by Phyllis Speidell

Photos by John H. Sheally II

Yellow daffodils spring up each year on wooded land around the Indiana United Methodist Church in Bowers Hill. Who planted the daffodils remains a mystery, but the resilient blooms symbolize the resiliency of the church as well as of the Nansemonds, Hampton Roads’ only remaining indigenous tribe of the Powhatan Empire.

Numbering about 1,200 members in the early 1600s, the tribe declined over that century. By the early 1700s, the surviving Nansemonds had become Christians and gravitated to the area northeast of the Dismal Swamp.

The church and the tribe share a historic connection. In 1850, the Methodist Church organized the church as a mission for the Nansemond Indians and built it between the Seaboard and Virginia Railroads in Bowers Hill.

By the mid-1800s, the area Nansemonds were farmers, watermen, shipyard workers and hunting guides scattered across Norfolk, Portsmouth, Chesapeake and elsewhere. The Basses, Brights and other Nansemond families settled in the Bowers Hill area.

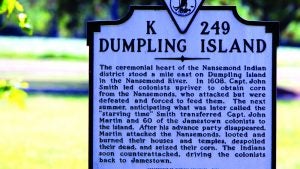

A historical marker about Dumpling Island, pictured on the opposite page. Dumpling Island was the ceremonial capital for the Nansemond Indian Tribe and the scene of attacks by English settlers. Below, an old bumper sticker supporting federal recognition for Virginia Indian tribes, which was finally achieved this January. (photo by John H. Sheally II)

“I know that my great-great-grandfather, Joseph Bright, was living in the swamp in 1850,” said Fred Bright, a Nansemond, retired nuclear engineering technician and avid genealogist well versed in the tribe’s history.

Bowers Hill was a logical place for the mission church until federal forces marching south burned it in 1862. After the Civil War, a new church opened near the current site on Indiana Avenue. Norfolk County’s Indian Public School No. 9, a one-room school for Indian children in grades one through seven, shared the site from the 1890s to 1928. At that time, Indian children could not attend white schools and were not welcome at black schools.

“My great-great-grandparents donated the land and helped build the first schoolhouse,” Bright said.

When the school burned about 1920, the students met in the church until a second fire destroyed the church a year later. A new school opened on its old site, and the current church building opened in 1924.

Throughout all the years and misfortunes, the church continues to consider itself the spiritual home of the Nansemonds. The tribe met there frequently during its re-organization years and its quest for state and federal recognition.

The Nansemonds’ quest for recognition was never easy, but in 1984, after years of denying the existence of native Indians, the Commonwealth of Virginia recognized the tribe that now numbers about 300, with members across the country. It took 34 years, however, to gain federal recognition with a bill signed by President Donald Trump in January 2018.

Virginia’s first registrar of the Bureau of Vital Statistics, Dr. Walter Plecker, served from 1912 to 1946 and created a huge obstacle to the recognition process. He was a eugenicist and advocate of white supremacy. He pushed for passage of the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 that criminalized interracial marriage and also required birth certificates to have only “White” and “Colored” designations. Many believe that Plecker altered existing birth certificates, as well, eliminating any reference to “Indian” because, he believed, there were no “true” Indians left in Virginia.

The long-term effect of altering birth records, often referred to as “clerical genocide,” greatly hampered the Indians’ quest for official records to document their lineage.

Earl Bass, chief emeritus, and his brother, Sam Bass, the assistant chief, as well as Bright, all grew up in Portsmouth and remember that their Indian heritage was rarely mentioned outside the home for fear of reprisals. Bright said that his grandmother “went to her grave saying there were no Indians in our family.”

The Nansemonds’ openness about their heritage blossomed in the post-Civil Rights era when Oliver Perry, from Norfolk and cousin to the Bass family, instigated the reorganization of the Nansemond Tribe in 1982 after researching his own connection with the tribe. A year later, the tribe organized formally as the Nansemond Indian Tribal Association, a non-profit organization.

Now, Sam and Earl Bass along with the current chief, Lee Lockamy, are working with the Bureau of Indian Affairs to learn what changes, restrictions and benefits federal recognition brings. The tribe is re-organizing as the Nansemond Indian Nation, no longer a non-profit, and will be led by a tribal council, a chief, an assistant chief, and a tribal administrator, a new position filled by Earl Bass, chief emeritus. The tribe must also develop a new business plan to meet the federal regulations.

So far, they know that recognition offers the opportunity to apply for grants aimed at, among other things, supporting the tribe’s governing structure as well as grants to finish and support Mattanock Town, a replica Nansemond village and cultural center on waterfront acreage at Lone Star Lakes in Suffolk. The tribe and community volunteers have worked for five years developing the project that will preserve the tribe’s heritage and history.

What recognition will not do busts a few common myths, Earl and Sam Bass explained. Casinos are not in their future, as the bill that granted them federal recognition also prohibits gaming of any kind. Tribe members will not be receiving a monthly check from the government, the Basses added, nor will recognition give them free federal health insurance or excuse them from paying taxes.

The Nansemonds also plan to open their genealogical records and hope to involve the general community in their programming via events and activities as well as powwows at Mattanock Town. Their short-term plans include a canoe and kayak ramp.

Many of the tribe trace their lineage back to and beyond William Bass, who appears on 1772 tax rolls as of English and Nansemond descent. That connection led to another recognition earlier this year. The Nansemonds can become the first majority Native American chapter of The Virginia Sons of the American Revolution. According to Michael J. Elston, national trustee and president of the Virginia S.A.R., the Nansemond Indian Chapter, upon approval, will be the first in the organization nationally, and the S.A.R. is excited about that prospect.

Who was Thomasina Jordan?

The bill that extended federal recognition to the Nansemonds and five other Virginia tribes was named for Thomasina E. Jordan. But who was she?

A resolution passed by the Virginia Assembly, upon her death, in January 2000, summarizes her achievements as an Indian activist and more. Raised in Mashpee, Mass., Jordan earned several advanced degrees, married and moved to Alexandria, where she was active in politics and was the first American Indian to serve, in 1988, in the Electoral College.

She served as the chairperson of the Virginia Council on Indians, founded the American Indian Cultural Exchange, was on the board of Save the Children and the National Rehabilitation Hospital, and received the Medal of Honor from the Daughters of the American Revolution.

She actively brought Indian issues to the forefront in the General Assembly, including legislation to correct birth certificates to identify Native Americans as such, and pushed the U.S. Congress to grant historic federal recognition to Virginia’s state-recognized tribes.